The Anton Collection

The Anton Collection

part of the Women in Art Sale, 17 January 2023

“I’ve got a consignment here that I think will be right up your street,” said James Bassam, the man responsible for putting together today’s auction. “Oh, yes?” I replied, with no great enthusiasm. One has to be on one’s guard on such occasions. I’m far too easily swayed, and I have, in the past, bought many entirely unsuitable items, having been persuaded that they would make wise investments. (Although I still maintain that, when the time is right to sell it on, The Brooklyn Bridge is set to bring me a great deal of money).

However, for politeness’s sake, I followed James out of the Wensum Room and into T W Gaze’s Store # 4 – or, as it seemed to me a few moments later, The Valley of the Kings. I stared about me in amazement. Even before he spoke again, I could see…well, I could see wonderful things. The spirit of Howard Carter (or perhaps the cartoon lovers equivalent, Reg) seemed to be hovering close at hand.

“I guess you’re familiar with Anton’s work?” said James.

“I am,” I said, “but…but…I’ve never seen so much of it.”

Which was true. But then nobody – apart from the artist’s family - had ever seen so much of it. What I looked on then, and what you see here today, is not simply a vast collection of Anton’s drawings: it is, perhaps, the most significant collection of original artwork by a major British cartoonist to come to auction in the last half-century.

So, I gazed…and was amazed.

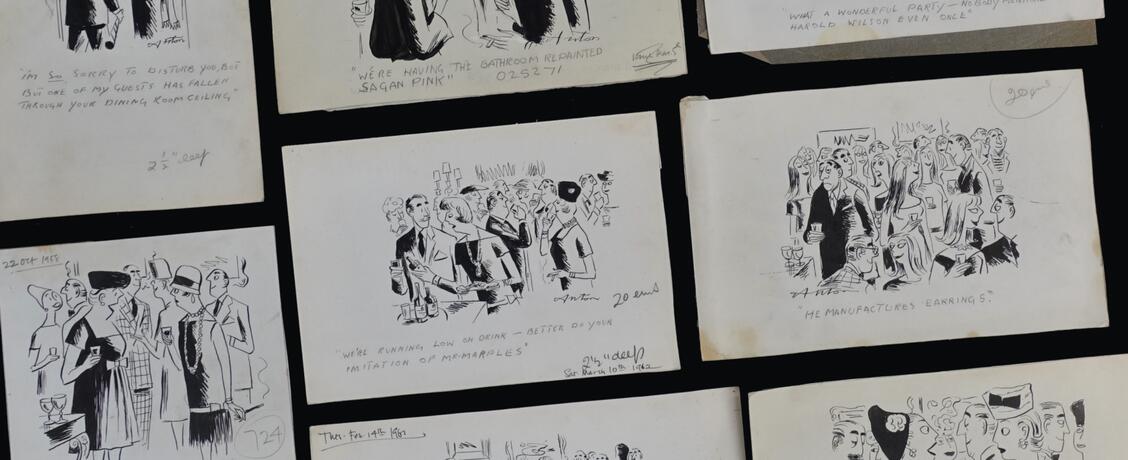

There were many hundreds of the original pen and ink drawings that had been reproduced in magazines and newspapers like Punch, Private Eye and The Evening Standard between 1938 and 1969. There were large, impossibly rare full-page gouaches from the days when a favoured Punch artist might only have a couple of opportunities a year to work in colour - one plate for the special Summer Number and another for the Christmas Almanack. There were early figure studies done while at art school; advertising commissions from Moss Bros; volumes of family photographs; letters; newspaper cuttings and back issues of various publications – some still going, but many so long defunct that even their publishers have probably forgotten their names.

But most of all there were the drawings. Those beautifully composed, elegantly crafted, richly dark pen and ink drawings, with their fresh, still-funny jokes. It was a fascinating collection. But then Anton’s story is fascinating – not least the fact that, perhaps uniquely among cartoonists, Anton was born twice…four years and 10,000 miles apart.

****

Anton was born on 24 July 1907 in Brisbane, Australia…and then a second time on 9 April 1911 in Cheshire, England. The reason for this apparent paradox isn’t hard to fathom: ‘Anton’ was the collective name adopted by the artists Antonia Thompson (later Yeomans) and her younger brother, Harold Underwood Thompson, when they decided to join forces and produce cartoons for the press in 1937. Playwrights had collaborated; so too had novelists. So why shouldn’t two cartoonists?

The fact that ‘Anton’ concealed the identity of two people was an open secret from the start. ‘Don’t ask how the partnership works out,’ they advised in the introduction to their first collection, Anton’s Amusement Arcade, in 1947. ‘We assure you it works out splendidly. You may be curious to know who does what, but why worry?’ Why indeed.

The venture was a success from the beginning and within weeks their work was being published by leading journals and newspapers. On 28 January 1938 the pair’s first cartoon appeared in Punch, the foremost humour magazine of the day. Punch was to be Anton’s most significant publishing partner and the magazine with which, above all others, the name ‘Anton’ would be associated; so much so, indeed, that when a second book, Low Life and High Life was published in 1952, it bore the legend: ‘By Anton of Punch.’

When Anton joined Punch in 1938, it was arguably at the height of its graphic powers, with artists such as Pont, Fougasse and Paul Crum among the star names whose ‘sketches,’ as the non-political joke drawings were known, enlivened the magazine and made its readership laugh. Happily, Antonia and Harold were not overshadowed by these stellar talents. The combination of detailed, but not over-fussy draftsmanship (shown to greatest effect when laid out as a generous half-page) and a wry, sometimes surreal sense of humour served them well. They were a palpable hit. As R. G. G. Price noted in his A History of Punch in 1957:

‘The jokes stayed good, volume after volume. The drawing was decorative, and the massed blacks showed up well on the page. The world of tall men politely inclining forward, of spivs and forgers, and waiters and duchesses and wonderful dining room tables was calmly, courteously mad.’

Antonia herself explained: ‘These are pictures about people who inhabit a certain world which may, or may not, exist. In general they are people with tendencies. They are social people. They visit the theatre, attend banquets and occasionally get married. For recreation they go in for everything from big game hunting to trying their skill at skating, dog breeding and in amusement arcades. They suffer the inconveniences of life fairly cheerfully. Finally and above all else, these people do tend to be afflicted with burglars.’

The outbreak of war in 1939 saw a major change in Anton’s circumstances. Before long Harold had joined the Royal Navy, while Antonia carried on alone, submitting drawings under the Anton banner and contributing to the war effort in her own way, wielding the pen rather than the sword.

A case in point is the 24 January 1940 issue of Punch. This number contained the cartoon that has a decent claim to be the finest of Anton’s career – it is certainly one of the most famous and is often anthologised. Antonia herself evidently looked upon it with some pride, since the original artwork can be seen framed on the wall in the background of a number of family photographs (included in this sale).

In the drawing, we observe that MI6 have supplied a modest, rather gormless looking clerk with a toothbrush moustache and dressed him up in a German military uniform hired from a theatrical costumier, so that he (very vaguely) resembles Adolf Hitler. One of the attendant spymasters says to him, rather casually: ‘Now, if we’re going to put this over properly, you’ll have to learn German.’ This drawing is rightly considered a classic of British pictorial humour although, alas! the original was not part of the archive and so (alas again!) it does not feature in today’s sale. (But don’t worry – there are many superb cartoons that do).

Although the siblings were reunited from 1945 until the late 40s / early 50s (some sources say Harold departed in 1949 for a full-time career in advertising, although Low Life and High Life from 1952 seems to credit them both) the 50s essentially belonged to Antonia alone.

As the years passed, Anton’s (by this time solely Antonia’s) style became simpler and the drawings brighter, with fewer of the rich, black blocks that Price so admired. Partly this was down to the natural evolution of the artist. Cartoonists tend to streamline and simplify as their careers progress; as they gain in experience and confidence, they often feel less need to strive for effect (the same process of reduction can be seen in the work of fellow Punch artists Pont and George Morrow, among others). Partly, too, it was down to the growing ascendancy of joke over drawing (of substance over style, if you like) which affected practically every cartoonist and art editor of the post-war world. Gone were the days when a feeble jibe about a servant’s aspirant H, or slightly sickly demonstration of ‘the funny things that children say’ could be rescued – or justified – by a fine piece of penmanship. Forget the beautifully shaded fireplace, or the details of the butler’s buttons: as the 20th Century progressed, a cartoon had first and foremost to make you laugh. And when joke supplants drawing in importance, there is another knock-on effect: the drawing doesn’t need to be anything like so large. And it is interesting to note that in the last few years of her working life, pocket cartoons (single panel, single column drawings first introduced by Osbert Lancaster in the late 1930s) made up much of Antonia’s output.

Happily, while Antonia’s drawing had always been good, it was equally matched by her wit, so the reduction in size didn’t matter so much: big or small, they remained funny. That’s why so many of her cartoons, whether the ornate half-pagers from 1938, or the simple ‘here’s-the-gag’ single panel sketches from thirty years later, still work so well today. I read every single joke while helping James to prepare these drawings for today’s sale - many hundreds of them - and I laughed a lot, which doesn’t happen very often. And I’m not alone in my estimate of her talents. This is what Joyce Grenfell had to say in her preface to High Life and Low Life:

‘Much as I love to look back through old Punch’s, I seldom smile. I admire Phil May, a beautiful draughtsman; I am soothed by the stability of Du Maurier’s world but I don't smile much. I never laugh at all. It is still a bit hit and miss now [written in 1952] but I find at least two drawings a week that give me pleasure and make me want to show them to someone else; and very, very often, one of these drawings is by Anton.’

More than fifty years after Antonia Yeoman’s death, that is still the case. But don’t take our word for it. Open a packet and take a look for yourself.

Today’s Sale

When the archive was first consigned to T W Gaze it was essentially as the artist herself had left it when she died in 1970, and most of the cartoons it contained had been divided up by subject area. This was fascinating in itself – who knew that forgers attempting to turn out dodgy banknotes would feature quite so heavily? But while such a logical, regimented system works well for the archivist, it is not ideal for the auctioneer looking to turn a large collection into buyable lots.

Unless Relate decided to hold its annual conference in Diss on sale day, for example, it seemed unlikely that many people would be keen to purchase a dozen variations on marriage counsellors and their clients. Similar problems arose when it came to missionaries being cooked in cannibal stewpots: there would be few chefs – and, logically, fewer still of their intended dinners – wanting nine or ten examples of this venerable (but now largely discontinued) cartoon genre. As for the many castaways marooned on remote, single-palm-treed desert islands (another time-honoured cartoon subject essayed to great effect by Anton) well…they would never get to hear of the sale in the first place.

Consequently, quite early on, the decision was taken to mix things up and turn the large number of individual specialized subject areas into general lots – with no more than one counsellor, one cannibal and one castaway per packet. We didn’t adhere to this rule in every case, so there are some lots that contain several drawings pertaining to golf, or motoring, or city boardrooms, or what have you. Where these fell naturally together, they have been lotted together, and we made a note in the catalogue to that effect.

So please take a good look at the lots on offer. Marvel at the skill of the drawing and enjoy the snap of the joke – you will see plenty of great examples of both in today’s sale. And you are unlikely to see anything like it ever again.

Beryl Antonia Botterill Yeoman (nee Thompson) 1907-1970

Harold Underwood Thompson 1911 – 1996

David Cook

(David Cook bought his first proper picture – a Kate Greenaway watercolour – in these rooms back in 1992. He is a collector of original cartoons and illustrations and writes about pictures, antiques and collectables).